Russell ‘Russ’ Henderson MBE

Russell Audley Ferdinand Henderson

Trinidad-born jazz pianist and leading figure in the steelband movement in Britain who helped set up the Notting Hill Carnival.

Russ Henderson, who has died aged 91, was an eloquent jazz pianist from Trinidad and a leading figure in the steelband movement in Britain. For more than six decades he used music as a focus for community cohesion and the bettering of race relations, and was directly involved in the establishment of the Notting Hill carnivalin London.

The idea of a carnival in Notting Hill came from the annual Lenten tradition of “playing mas” (masquerade) in the eastern Caribbean. In 1966 the community worker Rhaune Laslettinvited Henderson to bring a three-piece steel band to play for the first Notting Hill fayre and pageant, an event she had organised in conjunction with the London Free School and the photographer, writer and activist John “Hoppy” Hopkins. The small steel band arrived at Portobello Green accompanied by a crowd of regulars from the Coleherne pub, and after having played for some time in a standing position, Henderson suggested everyone should embark on a road march. The procession, joined by the public, was repeated the following day, and became the first manifestation of what has since grown into an international event attended by more than one million revellers each year.

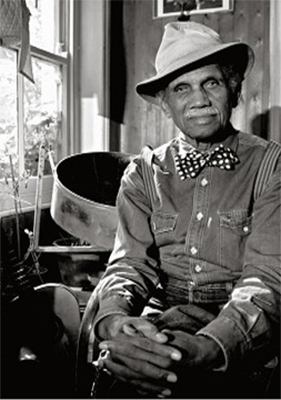

Russell at home.

Born in Port of Spain to Arnott, an accountant, and Evelyn, Henderson grew up in a middle-class environment and learned to play the piano by watching his two older sisters. When his mother organised dances, employing the local JazzHounds, their distinguished leader, Bert McLean, taught her son waltzes and hired him to play interval piano while he was still in short trousers.

In 1948 Henderson’s quartet won an island-wide musical contest and they subsequently shared a bill with Ray Nathan’s American Quartette, four African-Americans of Caribbean descent whose pianist was Wynton Kelly. Kelly became Henderson’s good friend and went on to make his name with Miles Davis. He taught Henderson to play Robbins’ Nest, the tune that became Henderson’s theme-song, and in turn Henderson passed on his new “calypso-jazz” concept to the visitors.

Henderson’s aptitude for spotting a cultural crossover was demonstrated for the first time when, during live gigs in Trinidad, he began to deliver calypso-tinged versions of the theme tune of the BBC comedy radio series Much Binding in the Marsh, which could be heard in the Caribbean through the BBC Overseas Service. The programme’s theme tune included a weekly rundown of news events, and Henderson’s version enjoyed great local popularity, especially as it took a dig at the upper-class British upper classes.

Jazzing it up on the piano.

In 1951, Henderson moved to Britain to experience the “mother country” and its accents at first hand. He intended to train as a piano-tuner but ended up playing the piano in Soho dives, where an eager and talented black youngster was just what was wanted to brighten up life in grey, austerity Britain. When he formed a nightclub trio with two fellow Trinidadians, Sterling Betancourt and Max Cherrie, the three of them “doubled” on each other’s instruments.

By 1952, they had introduced Trinidadian steel pans into their act. These were tuned percussion instruments, made by hammering out old oil drums into sections until the right pitch for each note was reached, and Betancourt was among the percussionists to introduce them at the 1951 Festival of Britain. At La Ronde, off Piccadilly, the musicians played the pans in a separate cabaret act, changing into tropical shirts to do so. Their adaptability ensured that the nightclubs provided them with a reliable home for many years, while Henderson and Cherrie diversified: each held long piano residencies at the Rockingham, a gay club in Archer Street.

Russell at his Tribute Concert in the Tabernacle, London.

Working with his fellow countrymen, Henderson played the piano for the calypsonian Lord Kitcheneron records and accompanied the singer George Browne(Young Tiger) in cabaret, but he was embraced by a prewar generation of Caribbean and African musicians, too. He played dances under the leadership of Bertie King, Freddy Grant, George Roberts, Joe Appleton and Leslie Hutchinson, especially for functions organised by Hugh Scotland to coincide with British and Caribbean public holidays.

At the same time, the increasingly popular sound of the steelpan was being heard amid upper-class chatter at places such as Esmeralda’s Barn in Knightsbridge, hunt balls and debutante parties in the shires, providing Henderson with a handy meal-ticket. When the trio performed for a royal garden party at Buckingham Palace, they made history as the first steel band to play for royalty.

Henderson toured in variety with the steelband, and did theatre and radio work. In 1957 he joined forces with the trumpeter Leslie Hutchinson to form the Hutchinson-Henderson All West Indian Band for a 13-week radio series. The band’s name was a misnomer as the two units played separately, both using material arranged by Rupert Nurse, another Trinidadian.

Russell at the Notting Hill Carnival

Generations of jazz lovers know Henderson as a pianist from two important London residencies, each of them lasting for 25 years. From 1962 Sunday lunchtimes at the Coleherne, an otherwise gay pub in Old Brompton Road, provided an exceptional opportunity for amateurs to sit in with him, backed by a plethora of percussionists, with figures as musically diverse as Joe Harriott, Graham Bond, John Surman, Davey Graham and Philly Joe Jones taking their turn. From 1971 the 606 Club in Fulham fulfilled a similar function, with the spotlight more frequently on Henderson and the chance to hear his understated piano playing, a style owing much to his lifelong hero, Teddy Wilson.

Henderson also lectured on the steel pan in schools and at the Commonwealth Institute in London. He organised workshops and larger percussion ensembles, while remaining in demand for social functions. He travelled regularly to Europe and, latterly, divided his time between London and Spain, returning to Trinidad each year for carnival. In 2006, he was appointed MBE for services to music.

He is survived by two sons, Pablo and Angus, from his partnership with Marie-Germaine Musso, and by a daughter, Alison, from an earlier marriage to Eve Rigby.

Russell Audley Ferdinand Henderson, musician, born 7 January 1924; died 18 August 2015.